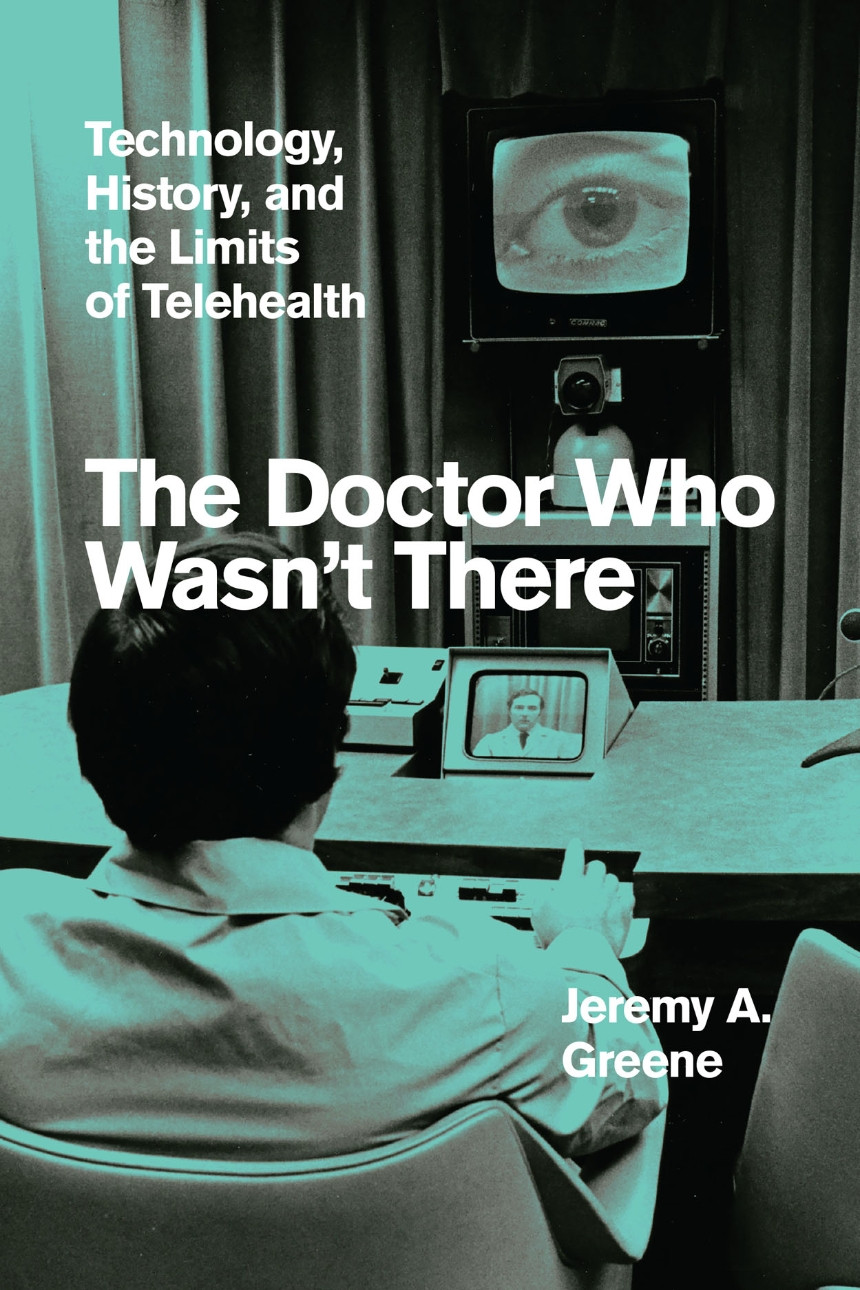

In 2022, Jeremy Greene, MD, PhD, a Greenwall Faculty Scholars Program Alum, published The Doctor Who Wasn’t There, an historical look at the emerging telemedical technologies of the last two centuries and the ways they have—and haven’t—made the positive impact that many hope for them.

Dr. Greene is both an historian and a physician. He practices internal medicine at a clinic in Baltimore, Maryland, where he has witnessed changes to the way doctors deliver care that have tremendous potential but were met with mixed reactions.

The Greenwall Foundation sat down with Dr. Greene to discuss the history of hype in telemedical technologies and what can be done to help them deliver on their considerable promise to increase availability, speed, and quality of care. The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

What moved you to write the book?

What first got me started was my colleagues talking about how much they hated their computers. We had this [then-new] thing called the electronic medical record that was supposed to help create more efficiency and allow for better care and ease of access to information. But it was actually doing the opposite, creating more labor, dehumanizing interactions, and taking doctors away from their patients.

I found myself drawn back to articles in medical journals from when the telephone was introduced, and realized that this electrical medium that promised instant connectivity had many of the same sort of hopes and fears around it that the electronic medical record had in the early 21st century. Why is it that every time we have a new medium of care, there’s a cycle of claims made about the brilliant new ways it will actually reduce labor, increase equity and access, and make medical care instantaneous? But at the same time, there are powerful fears about how dehumanizing it will be and distort the true nature of medical care. As it turns out, it’s often neither the sort of highest hopes or the or the darkest fears, but rather something quite lateral [that results].

The book talks about how, despite their hype, technologies haven’t reduced health inequalities. In many cases we’ve seen those inequalities worsen. Why might it still be worth believing in that promise?

In the social sciences and humanities and bioethics there’s a longstanding critique of a technological fix: Why do we look to technology to solve what are fundamentally social problems? One of the answers is that these technologies appear to be simpler solutions than [more directly addressing] these deeply intractable problems like inequity, racism, and xenophobia. And another, more cynical answer is that people can make money from technologies while claiming to solve social problems.

I would argue that these new technologies iteratively give the promise of a place to start doing work to undo inequality. I don’t suggest we short circuit the social problems, but technologies can be a way of rebuilding some optimism that something meaningful can be done rather than face an enduring fatalism. Even as the book looks at what are arguably a series of failed promises of producing equity and access to health care through communications devices, it is the case that all of these devices truly show some promise to increase equity and access to care.

Jeremy Greene, MD, PhD

Jeremy Greene, MD, PhD